For six months, an 8-year-old boy and his family from Alabama lived in the unrelenting grip of brain cancer.

Beau Brewer endured surgery, radiation and countless days in hospital rooms. So when the scan results finally arrived last week confirming that the tumor was gone, his parents -- Leslie and Matthew -- felt overwhelming relief.

"Horrific moments and images from [the] last six grueling months flashed before my eyes and for the first time I thought to myself, it's gone. That brain tumor that tried to take my child is really gone," Leslie, 37, told Newsweek.

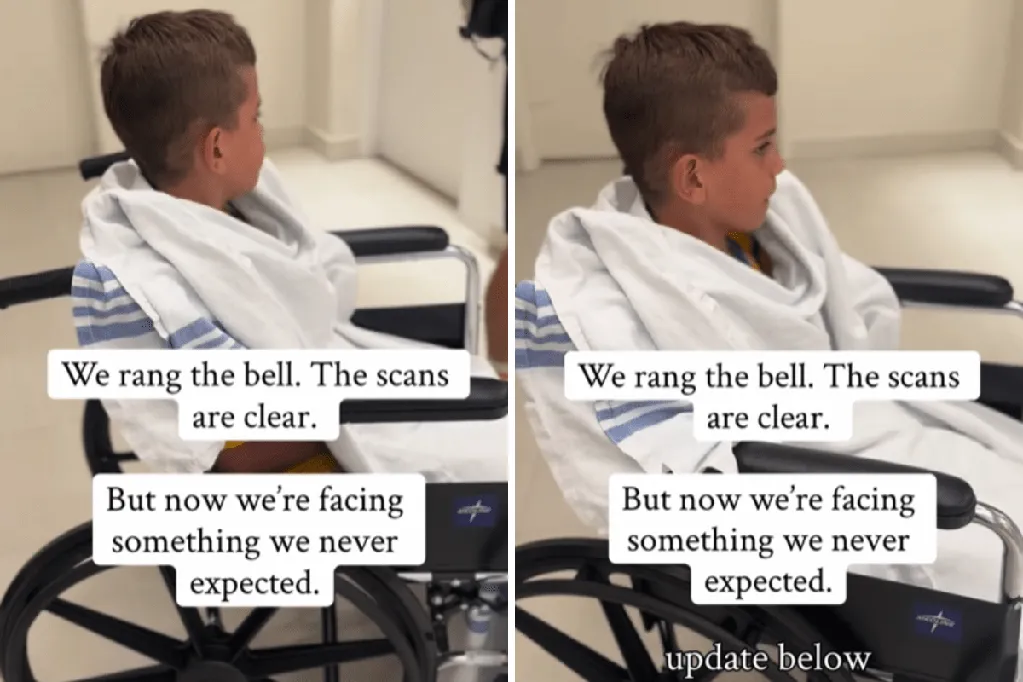

In that moment, the Brewers exhaled for the first time in months. They rang the bell. They cried. They celebrated this huge milestone. But now the family face a different kind of struggle.

In a reel posted on Instagram (@ask_the_np_mom), Leslie explained that Beau's behavior has changed significantly. A once playful boy is now battling rage, withdrawal and emotional turmoil.

"To be transparent," Leslie wrote in her caption, "Our brave survivor isn't thriving. He's drowning in anger, irritability and rigidity that is consuming his life."

Doctors have helped the family understand why. Beau's brain tumor, a grade 3 ependymoma, was "stuck like a sticker on a window," Leslie explained.

Surgeons had to decide between manipulating healthy brain tissue to remove it or leaving part of the tumor in place and risking regrowth.

The procedure saved Beau's life, but it also caused posterior fossa syndrome, a condition linked to damage in the cerebellum -- the region that coordinates movement, speech and emotional regulation.

"After surgery, some kids suddenly have trouble talking, seem emotional or flat and may have trouble with balance or movement," Leslie explained. "Most kids slowly recover over weeks to months, though some speech or emotional changes can be permanent. It took Beau weeks to start speaking and walking, but the emotional changes have been the hardest by far."

Today, Beau's challenges extend far beyond the physical. He struggles to connect with his siblings -- Emerson, six, Worth, four, Banks, three, and Mac, one -- and is easily overwhelmed by noise or interaction.

Leslie and Matthew are now grappling with balancing grief and joy equally.

"I love the liturgy from [author Douglas Kaine McKelvey's work] 'Every Moment Holy' and pulled inspiration from it to express our feelings in my post," Leslie said. "When things are hard, like brain cancer, we cannot shrink from the necessary experience of grief. We also can't be so consumed with loss and lack that we miss entirely the living gifts this day might hold."

Those reminders appear in small glimpses: a laugh overheard at school, Beau choosing to climb stairs instead of taking the elevator or a spontaneous hug for his little brother.

"These are gifts that must act as reminders that the Lord is sustaining, healing and providing all we need to keep us moving forward on hard days," Leslie said.

Leslie hopes her family's story can bring comfort to other parents navigating life after childhood cancer.

"I want them to know they're not alone," she said. "Someone once told me that behavioral and psychological problems after treatment [are] like the main road has been destroyed. Some roads are closed some bumpy and it will take time to map it, but they're making a road to set them up for success in survivorship."

"That really helped give us a picture of what's going on inside a child's mind after treatment," Leslie continued. "I hope it encourages other parents that our children are capable of making new maps to thrive in life after cancer."