The United Kingdom doesn't have a reputation for glamorous, eye-catching basketball courts.

As content creators SBB (Simply British Ballers) highlighted, there are some unique courts across the U.K., including Butts End, located in Hemel Hempstead, a town 25 miles northwest of London. But distinctiveness is not always a positive. A small concrete square, after all, makes for restrictive play.

The Butts End basketball "court," to stretch the meaning of the term to its limit, calls attention to some of the issues the sport has in the U.K. -- of which there are plenty.

Basketball fans globally have had their eyes on a highly competitive NBA Finals matchup between the Oklahoma City Thunder and the Indiana Pacers. The best-of-seven series continues Thursday with Game 6 and has attracted millions of television viewers during its first five games. The entertainment value has been high throughout the United States and Canada, despite the two small-market teams.

Basketball isn't as welcome on the other side of the globe. It is England's second-most popular team sport behind soccer, according to Basketball England. There has been talk of establishing a London and/or Manchester franchise in the developing European league coordinated by the NBA and FIBA, which is good news. But British basketball is bitterly divided, and when it comes to U.K. funding for the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, basketball is behind badminton, weightlifting and shooting.

"I'm tired of basketball being s -- in this country," Sam Neter, who runs the website and foundation Hoopsfix, told The Athletic. "At some point, it has got to change, and it's not going to change by all of us sitting around saying how bad it is."

Neter has been on a mission to "change the game" since Hoopsfix first launched in 2009 and has been involved in refurbishing two basketball courts in May alone -- one on the south coast in Brighton, often referred to as "England's Miami," and the other at Turnpike Lane in north London.

But can these colorful designs help awaken a country considered a sleeping giant of European basketball?

Emerging from the London Underground, Turnpike Lane has a bustling shopping area in either direction: cafés, supermarkets and takeaways with plenty of people mulling about. At first glance, the central location can be any suburb in the English capital.

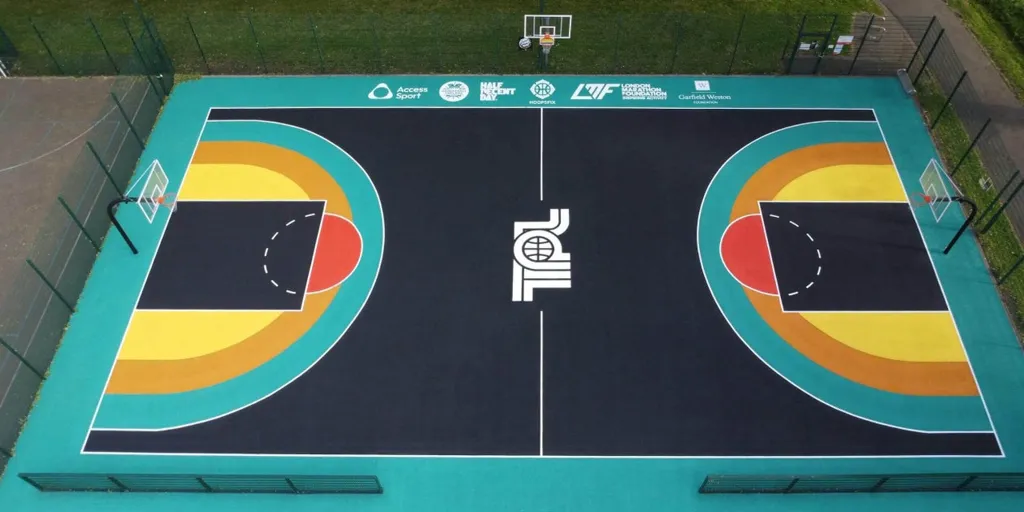

But a stone's throw away from the station is Ducketts Common, home to recently renovated courts. Highlighting the extent of their transformation, an old, concrete-gray court sits horizontally behind two revamped courts that are awash with color. The turquoise, orange and yellow add extra vibrancy to a red-hot summer’s day.

Wheelchair basketball, children’s clinics, a 3-point contest and a dunk show took place during an official unveiling on May 29. The audience consisted of stakeholders, volunteers and eager hoopers waiting to play.

Among them was Sam Sure, a 34-year-old designer who worked on the Brighton and Turnpike Lane courts.

"Turnpike Lane is an old-school court, so I wanted it to be retro. I wanted the colors to be old-school-looking," Sure said. "That was the main motivation, and also, I wanted the colors to be unique to this court and not like any of the others I have done."

Sure's first design was a court in southeast London, Deptford Blue Cage, which he said reminded him of New York. Further jobs followed. Once a signed music artist and songwriter -- his song "Hunger" has more than 8 million streams on Spotify -- Sure organically moved into design after the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I'd always made my own videos, designed my own artwork, and I started in COVID this brand, Half Decent Day, making clothes. The basketball courts were a tag onto that in the beginning, and now they run side by side," Sure said. "I just love art on any level, and I totally make art for art's sake. It was never supposed to be something I made money out of. ... It's much more of a passion project than anything else."

Sure plays basketball regularly and uses his knowledge to ensure his designs are playable and functional.

"I come and play at the court, meet the locals, talk to everybody and try and find out what they want and what represents the area," he said. "I try to be unique each time and try to give each community its own identity.

"If they feel like they have ownership of the court, then it becomes part of the fabric of the area, and they look after it more. There is pride there."

Court refurbishments usually take a year minimum, Sure said. Brighton took 12 months, and Turnpike Lane took 18 months. Costs range roughly from £50,000 ($67,465) to £100,000 ($134,937).

But the benefit to the community can be priceless.

"I'd spent my life working in music and performing, and the buzz I get from this is way bigger," said Sure, adding that renovations "really impact the areas" in question. "These areas that I have done (court refurbishments) are all deprived areas."

Hoopsfix's first court renovation was Clapham Common in south London, one of the city's largest public spaces. Featuring a full court and two side-by-side half courts, Clapham was completed in November 2021.

The court has SBB's seal of approval. Denzel Kazembe and Behrad Bakhtiari, who first started reviewing basketball courts online in college, gave Clapham 10 out of 10, with top ratings on the backboards, rims and court competition.

"It was kind of a milestone for British basketball," Kazembe said. "I'm from east London, but the fact that someone from east London now knows about Clapham Common and is traveling there to join that community speaks volumes. You can see the nuggets of the community from beforehand, from the people that turn up with a speaker and mic to the rules specific to the court."

Renovated with the assistance of the NBA, Foot Locker and Hoopsfix and designed by Pete Simmons of creative agency 5or6,Clapham took three years to finish. The 280 seats that surround the main court are the highest number of any outdoor court in the country,Neterclaims.

Situated near a comparatively humdrum skate park in the 220-acre common,the black and blues of Simmons’creation stand out.

“When we did it,it wasn’t just about renovating it.We produced a 5,000-word guide on how to renovate a local basketball court with everything we’d learned in the process,”Neter said.“We released an hour-long video on YouTube that vlogs the entire process,showing everything we did along the way.”

“That’s where I see the foundation being able to have an impact.Ultimately,we’re never going to have the impact on British basketball if it’s just us.”

Getting a project like Clapham over the line came with various challenges,such as realizing a common has stricter guidelines than a park.

Funding is also a challenge.An annual basketball game helps Hoopsfix with its funding goals.The Hoopsfix All-Star Classic,held since 2014,spotlights some of the best under-19 talent in the country.Some former participants have made it to the NBA including Jeremy Sochan (San Antonio Spurs) and Tosan Evbuomwan (Brooklyn Nets).

The event has allowed Hoopsfix -- its social media accounts combined feature nearly 100,000 followers -- to fund court refurbishments,in addition to collaborators.For Clapham,this was a £5,000 contribution;the rest of the funding fell into place.

"I got serious about wanting to renovate a basketball court in 2018. So, we put out a thing on social media asking people where we should renovate," Neter said. "We had hundreds of responses, and Clapham Common was by far the most requested court.

"We had no idea how to do it, or how we were going to raise the money to do it. We engaged with the council and started putting together plans. By the end of 2020, we were introduced to someone at the NBA who was working with Foot Locker. They were looking for a court to refurbish that year, but they couldn't find a court within the timelines. We had all the council permissions to do it; we just didn't have the money, so it worked out perfectly. It's one of them things that you put out into the universe, and it comes back to you in some type of way."

Clapham's success equated to more requests for Neter to help refurbish other courts, as was the case with Brighton (completed in May this year). It led to a three-year partnership with Access Sport, a charity that aims to increase inclusion in community sport. That partnership includes an agreement to renovate five courts in London: Burgess Park and Turnpike Lane (completed), Gibbons Park and Hornfair Park (to be completed) and another location to be determined. Access Sport and the London Marathon Foundation have a £1.6 million fund invested in basketball and cycling activities across London.

There remains a long list of problems with British basketball, including expensive facilities, a shortage of volunteers and high-potential players leaving to play in the United States and elsewhere in Europe. But beautiful courts, which help the grassroots thrive, could be a seed for better things to come.

"It's very much a step, not a completed thing. It's very much straight onto the next one," said Neter, who added there have been plans discussed for more renovations as well as the towns of Bristol and Swindon in southwest England. "It's satisfying seeing it but it just adds more fuel to the fire to do the next one."