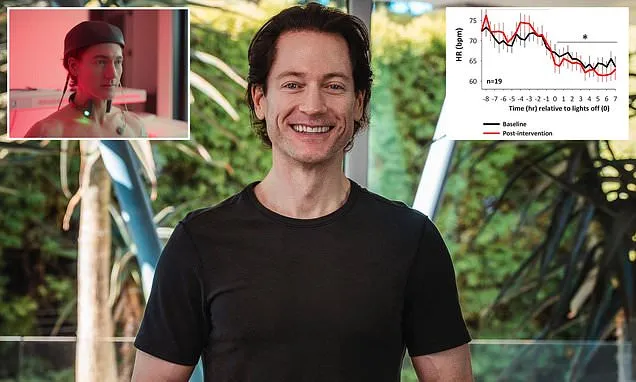

Biohacker Bryan Johnson has shared a lifestyle tip backed by a groundbreaking study pointing to the right time to eat before bed.

Johnson, who is known for his unconventional quest for immortality at any cost, shared a new study by Northwestern University researchers that concluded a powerful means of maintaining heart health and improving metabolism: stop snacking three hours before bedtime.

'A new study out confirms this is the right thing to do,' the 48-year-old said.

While Johnson says he fasts for eight hours before bed, he suggests most people can benefit from three hours.

In the latest study, obese people who adhered to an overnight fasting plan that involved not eating within three hours before bed saw their resting heart rate drop by five percent, a sign of reduced cardiovascular strain and improved recovery during sleep; levels of the stress hormone cortisol fell and blood glucose modulation improved.

Despite the significant improvements in cardiovascular and metabolic health, the study found no significant changes in BMI or waist circumference in either group. The cardiometabolic improvements happened independently of weight loss.

This is a form of intermittent fasting, which works best when it syncs with the body's internal clock. The idea is to eat when the body is primed to process food during daylight hours and give it a break when it is preparing to rest.

Metabolism runs more efficiently earlier in the day; insulin sensitivity is higher and overnight fasting allows cells to repair themselves. By aligning when you eat with how your body is built to function, you're not just eating less; you're eating at the right time.

All of Bryan Johnson's food consumption is compressed into a daily six-hour window, typically between 6 am and 11 am, which results in an 18-hour daily fast.

'To find your optimal window, start by consuming your latest meal three or four hours before bedtime, and then work backward in one- or two-hour increments,' Johnson wrote on X.

Time-restricted eating keeps gaining traction, with research showing it can boost heart and metabolic health as effectively as standard calorie counting. But most studies zero in on how long people fast, overlooking a crucial detail: whether the fasting window aligns with their sleep cycle, a key factor in how the body regulates metabolism.

Dr Daniela Grimaldi, a neurologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said in a statement: 'Timing our fasting window to work with the body's natural wake-sleep rhythms can improve the coordination between the heart, metabolism and sleep, all of which work together to protect cardiovascular health.'

The study, published this week in the journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, enrolled 39 obese adults ages 36 to 75; 21 followed an extended fasting protocol of 13 to 16 hours and 18 followed a control condition where the fasting length was 11 to 13 hours for 7.5 weeks. Both groups dimmed the lights three hours before bedtime to initiate melatonin production.

Participants in the extended overnight fasting (EOF) group showed strong adherence to the protocol, with 88 percent compliance to the fasting window. On average, they extended their overnight fast to 14 hours and 51 minutes, compared to just 11 hours and 50 minutes in the control group.

They also maintained a robust four-hour and 24-minute fast before bedtime versus 2 hours and 41 minutes in the control group, demonstrating a significant behavioral shift in aligning food intake with the sleep cycle.

At its core, Johnson's philosophy, which he calls 'Don't Die,' is to outsource decision-making to data and algorithms, removing human whim from the equation to reach a healthy, advanced old age.

The longer fasting group experienced notable improvements in heart rate regulation.

- Nighttime heart rate dropped by an average of 2.3 beats per minute, a signal that the heart is under less strain, the nervous system is better regulated and the body is recovering more effectively during sleep.

- Daytime heart rate increased by 1.5 beats per minute, suggesting a restoration of healthy day-night rhythm.

- Heart rate dipping - the natural drop in heart rate during sleep - improved by nearly five percent in the experimental group, compared to a slight worsening in controls, signaling that the heart was getting the nightly rest it needs, the nervous system was balanced and the body was better aligned with its natural circadian rhythm.

Blood pressure also improved. Nighttime diastolic pressure, the bottom number on the reading, fell by 1.8 mmHg in the longer fasting group, while it rose in controls. Diastolic blood pressure dipping increased by 3.5 percent overnight, signaling that the cardiovascular system is under less strain.

Crucially, about 60 percent of the longer-fasting participants who began the study with unhealthy non-dipping blood pressure patterns converted to healthy dipper status, compared to only a quarter of participants in the control group.

These changes were accompanied by a measurable reduction in nighttime cortisol and a shift in heart rate variability toward healthier parasympathetic dominance during sleep.

The experimental group's [left] glucose levels dropped after the intervention, meaning they cleared sugar more efficiently. B shows the control group's glucose levels rose, indicating their glucose tolerance slightly worsened.

Cortisol is the body's primary stress hormone, and it's meant to be low at night to allow for deep restoration.

When nighttime cortisol remains elevated, it keeps the body in a state of low-grade alertness, disrupting repair processes and impairing immune function.

While the experimental condition did not change overall caloric intake, BMI or waist circumference, it produced meaningful improvements in blood sugar regulation.

Following a glucose tolerance test, mean glucose levels dropped in the experimental group while they rose in controls.

Early insulin secretion, measured by the insulinogenic index, improved in the fasting group but declined in controls, indicating better pancreatic function and more efficient glucose handling—key factors in reducing diabetes risk.

Johnson said: 'While the three-hour pre-bed limit showed significant benefits in this trial, individuals who are already metabolically healthy may achieve further improvements and require a more stringent limit.'