When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

BRING ME THE HEAD OF JOAQUIN MURRIETA: The Bandit Chief Who Terrorized California and Launched the Legend of Zorro, by John Boessenecker

Blood and treasure alike poured out of the California gold rush, a jackpot moment when the dream of striking it rich was somewhat diminished by the imminent risk of being knifed, shot or smashed over the head with a whiskey bottle.

Most of the violence in and around the California mining camps was spontaneous, and most of the theft nonviolent. But the bandit gangs that terrorized El Dorado, depriving unwary prospectors of their precious nuggets and quite often their lives, were an unwelcome exception to this rule. And unlike later and more beloved Old West outlaws, they targeted random individuals, not banks, trains or Wells Fargo stagecoaches. Hardly folklore material.

Joaquin Murrieta is different. That Mexican-born bandit cut a bloody path through the Sierra Nevada foothills with his gang of rowdy pistoleros in 1853, and for a handful of interesting reasons his legend has lived on in places as diverse as early-20th-century pulp fiction (as the putative basis for the aristocratic masked avenger Zorro) and the Chicano social-justice movements of the 1960s and '70s. In "Bring Me the Head of Joaquin Murrieta," the frontier historian John Boessenecker demonstrates just how far the reputation of "America's most renowned Latino outlaw" has strayed from fact.

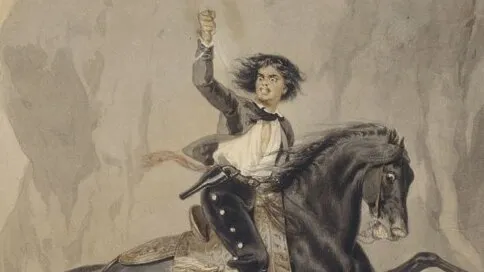

The popular image of Murrieta, a product of fanciful 19th-century artist renderings and adventure fiction, is a vivid one. He wore silver-buttoned calzoneras (split-leg trousers) and rode like the wind, his long black hair swirling. He moved so fast, draped in a thick serape, as to seem bulletproof to hapless pursuers. He was charming and debonair; the vilest murders associated with him were actually the work of a sadistic henchman known as Three-Fingered Jack. There were even rumors that when Murrieta was killed, in 1853, by a posse of "California Rangers," he had been plotting to overthrow the new state's Anglo government.

Boessenecker, author of some dozen works of frontier history, vouches for Murrieta's snazzy pants and horsemanship but dismisses most of the rest. His gang "rarely numbered more than a dozen men at a time, and he certainly did not attempt to lead an insurrection in California." Three-Fingered Jack (a.k.a. Bernardino Garcia) was indeed a bloodthirsty goon, but Murrieta (who didn't even have black hair) did plenty of his own killing too. And he did not taunt his pursuers with handwritten witticisms because he was illiterate.

Little is known about Murrieta's early life. He arrived in the American Southwest in early 1849, at around age 20, and briefly settled in the mostly Mexican camp of Sonora, Calif. Boessenecker's fluent descriptions of this "collection of canvas tents and brush huts" along a tributary of the Tuolumne River help compensate for the dearth of information about what Murrieta did there.

A comparison of relevant crime statistics helps paint the picture too. The annual homicide rate in present-day Chicago is around 20 per 100,000 people. In 1850 alone, 19 murders were committed in Sonorian Camp -- population, 5,000.

The Murrieta of legend was an honest man who turned to banditry after being violently assaulted repeatedly by gangs of white men, a sequence of provocations that included the assault of his bride, Rosa. Although Boessenecker doubts that any of these incidents occurred exactly as described, he is certain that Murrieta endured racist abuse from Anglos and "developed a profound hatred for them."

But although Murrieta's depredations against white men generated contemporary outrage, he also targeted fellow Mexicans and Californians of Mexican ancestry, and nearly half of his gang's murder victims were Chinese Americans, who rarely used guns or horses.

Murrieta's deadliest attack was the Feb. 21, 1853, massacre of eight Chinese miners at a ferry crossing on the Stanislaus River. His killing spree put such fear into the Chinese prospectors of Calaveras County that an undetermined number of them quit their claims and moved to cities.

Boessenecker, who is also a trial lawyer, draws heavily on the digitized newspaper archives unavailable to previous generations of scholars, allowing him to establish accurate timelines and make some other useful corrections to the record; however, his 459-page account would have benefited from some judicious editing. It is thickly padded with verbose quoted passages and tales of other bandits with names like Mountain Jim, Dutch Fred and Salomon Pico—history as one damned thug after another, as Arnold Toynbee might have said it. The historical Murrieta, obscure enough to begin with, fades even deeper into the background.

Lost amid all the forensics and yarn-spinning is the question of why he matters. Boessenecker ably exposes the enormous gap between the myth of Murrieta and the man. But the falsehoods surrounding outlaw folk heroes are often less interesting than the context in which they take hold and why.

Murrieta's rise to fame resembles that of Billy the Kid, whose enduring celebrity also grew out of a semi-fictional "biography" written by a down-on-his-luck newspaperman. I would have gladly traded three or four tales of angry lynch mobs for some of Boessenecker's insights on Old West mythmaking.

Murrieta's legend is inseparable from the racial tensions that led to California's 1855 passage of the Anti-Vagrancy Act, also known as the Greaser Act. That increasingly lopsided conflict is only sporadically acknowledged in this account, dulling its impact. One cannot understand, much less redefine, a larger-than-life figure without grappling with the question of why he got so big in the first place.

BRING ME THE HEAD OF JOAQUIN MURRIETA: The Bandit Chief Who Terrorized California and Launched the Legend of Zorro | By John Boessenecker | Hanover Square | 496 pp. | $32