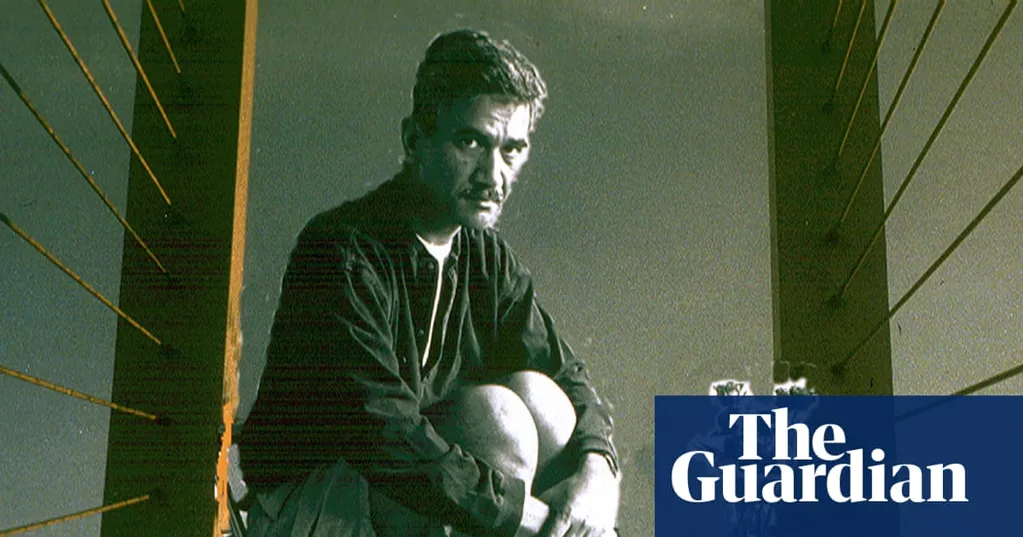

When the artist Sunil Gupta found out he was HIV positive in July 1995, making a collage helped him to process how he felt. He used an image of himself taken on the day of his diagnosis clutching his knees and looking defiantly into the camera, then placed it, using Photoshop, between the bars of the M25 bridge crossing, which look as though they're imprisoning him. "It was the day my life changed," he says.

"Photography was a great tool for therapy," Gupta says, and collaging "was very freeing, to get rid of those boundaries and put elements together." On his new Apple computer, he merged low-resolution photographs he'd taken of posters and graffiti in Berlin; a zoomed-in picture of a 1930s gay bar the Nazis closed down; self-portraits and scans from books. He explored queer relationships, migration and his concerns around Thatcher taking Britain into Europe. "All of the messaging at the time, very similar to now, was about being a stranger in a strange land," says Gupta. "I've been here since the 70s and I'm seventysomething but I still feel precarious."

His resulting series, Trespass (1992-95), forms the anchor point of a new exhibition about collaging, I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, at Autograph gallery in London, which looks at how images can be deconstructed and reappropriated to give them new meaning. In more than 90 works by 13 contemporary artists, photographic truth is called into question.

Popularised by artists in the early 20th century, collage got its name from the French term papiers collés to describe pasting paper cut-outs on to surfaces. But curator Bindi Vora wants to dispel the "misconception that collage can simply be a cut-and-paste type of practice." She has included tapestries by American textile artist Qualeasha Wood, whose self-portraits reference Ozempic and digital overconsumption; and Kenyan artist Jess Atieno's woven pictures, which challenge east Africa's colonial archives by using postcards, maps, and images of agriculture where photographs don't exist.

Indigenous Australian artist Brook Andrew's sapele wood sculpture unites images from queer and colonial histories. Henna Nadeem's newly commissioned photomontage links landscape imagery with Islamic patterns; while Sim Chi Yin's glass lantern slides from the late 19th and early 20th centuries show scenes from British Malaya that she has digitally altered to include her socialist grandfather, who was executed, and her son, who was born during the pandemic.

A 22-minute silent film by Wendimagegn Belete gives faces to the freedom fighters in Ethiopia who fought against Italian colonisation between 1935 and 1941. "There are so many pockets of these histories that are just not talked about," says Vora. "I think it becomes quite important in the conversation around what is propelled into the spotlight and what histories are marginalised."

Collaging becomes a means of disrupting the status quo. Kudzanai-Violet Hwami distorts her figurative paintings with visual fragments - classical and religious subjects as well as images of nature (she found family members posing beside plants in her family albums) - to figure out her identity as a Black, queer woman. Glitches and areas of pixelation express changes in consciousness and the forging of a digital identity.

Sabrina Tirvengadum keeps mistakes in the AI-modelled photographs of her ancestors that explore the fractured history of Mauritius, which was shaped by indentured labour. In rose-tinted portraits, her family sometimes have six fingers, while the Aapravasi Ghat staircase - which was the arrival point in Port Louis for more than 462,000 labourers, who worked for free or a low wage in a similar style after slavery was supposedly abolished - has two more steps than it should have done. "What I love about AI is that it gives me the glitches, like in history, when things are not quite right," says Tirvengadum.

The artist had to overcome AI's racial bias to create imagined portraits of her family where images don't exist. When she started using the tool in 2022, "I noticed that it wasn't able to generate people that looked like me when I typed in 'Indian', it would come up with Native Americans and they were very racist, stereotypical images," says Tirvengadum. She says that this has since changed.

Tirvengadum visited Mauritius, during the pandemic, for the first time in 14 years "to reconnect with my family by taking photographs of them." In albums, "I got to see photos that I hadn't seen; I saw what my grandfather looked like for the first time." Using AI to collage, the artist found a vocabulary when words weren't always available.

Historical maps play an important role in the exhibition: Reena Saini Kallat draws on her family's experience with partition in India, looking at political borders and the power of a passport; while Arpita Akhanda threads colonial maps through family photographs, to represent the missing time when her politically active grandfather would cross from West Bengal into India. Meanwhile, Sheida Soleimani, who runs a wildlife rehabilitation centre, links political exile from Iran with the care of injured migratory birds.

To understand the impact of diamond mining in southern Africa, Thato Toeba turned to public records where he found Horace Nicholls's photographs of the second Boer war. Nicholls was obsessed with horses, which he captured over the bloodshed and violence, contributing to the erasure of Black people in the archives.

Toeba's collages are full of double meanings: Man on Fire reflects on the brutal death of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, a church-going Mozambican man, who was burned to death during a rise of xenophobic violence in a Johannesburg township in 2008. Several men hold their hands up to the sky in a gesture of surrender but also to praise. In the centre is the portrait that was circulated by Nhamuave's family to remember him, not for the devastating death that he succumbed to, but to think about who he was as an individual.

It is a show that considers the missing chapters and histories in the archives, and how they might be brought into being - a debate that the curator says is very much alive. "We've seen a lot of shows historically that have dealt with works made by artists in the 1940s and 50s," says Vora. "This is very much a kind of contemporary conversation."