Mattathias Schwartz and Zach Montague cover the federal courts.

More than three dozen federal judges have told The New York Times that the Supreme Court's flurry of brief, opaque emergency orders in cases related to the Trump administration have left them confused about how to proceed in those matters and are hurting the judiciary's image with the public.

At issue are the quick-turn orders the Supreme Court has issued dictating whether Trump administration policies should be left in place while they are litigated through the lower courts. That emergency docket, a growing part of the Supreme Court's work in recent years, has taken on greater importance amid the flood of litigation challenging President Trump's efforts to expand executive power.

While the orders are technically temporary, they have had broad practical effects, allowing the administration to deport tens of thousands of people, discharge transgender military service members, fire thousands of government workers and slash federal spending.

The striking and highly unusual critique of the nation's highest court from lower court judges reveals the degree to which litigation over Mr. Trump's agenda has created strains in the federal judicial system.

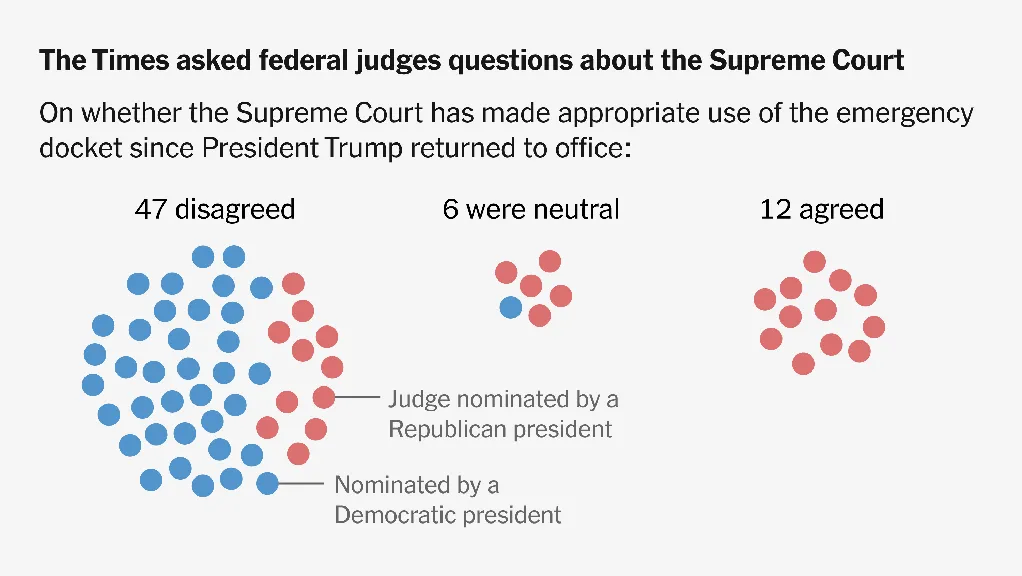

Sixty-five judges responded to a Times questionnaire sent to hundreds of federal judges across the country. Of those, 47 said the Supreme Court had been mishandling its emergency docket since Mr. Trump returned to office.

The judges responded to the questionnaire and spoke in interviews on the condition of anonymity so they could share their views candidly, as lower court judges are governed by a complex set of rules that include limitations on their public statements.

Of the judges who responded, 28 were nominated by Republican presidents, including 10 by Mr. Trump; 37 were nominated by Democrats. While those nominated by Democrats were more critical of the Supreme Court, judges nominated by presidents of both parties expressed concerns.

In interviews, federal judges called the Supreme Court's emergency orders "mystical," "overly blunt," "incredibly demoralizing and troubling" and "a slap in the face to the district courts." One judge compared their district's current relationship with the Supreme Court to "a war zone." Another said the courts were in the midst of a "judicial crisis."

The responses to The Times serve as the most comprehensive picture to date about the extraordinary tensions within the judiciary, hints of which have begun to spill out publicly.

At a hearing in September, Judge James A. Wynn Jr. of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit said his court was "out here flailing" as it tried to apply vague emergency rulings from the Supreme Court that left judges "in limbo." Ruling on a different case, Judge Allison D. Burroughs of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts noted that the emergency orders "have not been models of clarity."

The Supreme Court has so far issued emergency orders in about 20 cases involving the Trump administration's policies. In at least seven of those orders, the majority offered no reasoning for its decision.

At public events, some Supreme Court justices have defended their use of the emergency docket as a legitimate response to the increase in swift presidential policy-making by executive order, as opposed to legislation passed through Congress. Offering extensive reasoning or explanation, they argued, would risk locking the court into a position that might not turn out to be its final view.

A spokeswoman for the Supreme Court did not respond to a request for comment.

The Times reached out to more than 400 judges, including every judge in districts that have handled at least one legal challenge to a major piece of Mr. Trump's agenda.

Most of those who declined to participate did not give a reason. Others said they did not think it was their place to judge the work of the Supreme Court.

The judges who responded may not represent the views of the entire judiciary, but to have even several dozen judges out of the nation's more than 1,000 district, appellate and senior judges express such concern about the Supreme Court's behavior is highly unusual.

Forty-two judges went so far as to say that the Supreme Court's emergency orders had caused "some" or "major" harm to the public's perception of the judiciary. Among those who responded to the question, nearly half of the Republican-nominated judges said they believed the orders had harmed the judiciary's standing in the public eye.

Twelve judges who responded to the questionnaire said they believed the Supreme Court had handled its emergency docket appropriately. But only two said public perception of judges had improved as a result of how the Supreme Court had handled its recent work.

It is "of surpassing historic significance" that so many sitting judges have chosen to weigh in publicly about the Supreme Court, said J. Michael Luttig, a former federal judge who served as an assistant attorney general under President George H.W. Bush.

The code of conduct for federal judges requires them to act in ways that promote "public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary." They seldom comment on public controversies and almost never share their views of Supreme Court jurisprudence outside of the carefully chosen words of their written opinions.

Judge Luttig is a critic of the Trump administration's interpretation of the Constitution who is in frequent contact with sitting judges from across the political spectrum. He said he believed the views expressed to The Times were broadly representative of the lower courts as a whole.

"I can't think of words to capture the significance that federal judges themselves have to speak out,"

he said,

"because the Supreme Court has given them no choice but to speak out."

'An Atmosphere of Disrespect'

The emergency docket is known to its critics as the shadow docket, and its rise as a flashpoint for tensions in the judiciary coincides with the Supreme Court's increasing use of it in ways that have benefited Mr. Trump's agenda.

Time and time again, district court judges have imposed blocks on expansive policies issued by Mr. Trump's administration, rulings that have been upheld by the appeals courts, only to have the Supreme Court remove them with an emergency order. Mr. Trump has benefited from nearly all of the Supreme Court’s rulings on emergency applications since his return to office.

For now, his administration can withhold some forms of congressionally appropriated funds, send undocumented immigrants to dangerous places such as South Sudan and use race as a criterion in making immigration stops, all because of emergency orders.

Some of the judges who responded to the Times questionnaire expressed concerns with the substance of the Supreme Court’s orders, fearing critics would see partisanship in the justices’ consistent siding with the president over lower court judges. Similar views have been aired in dissents from the Supreme Court’s liberal wing, which have called pro-Trump rulings by the majority “misguided,” “dangerous” and an “existential threat to the rule of law.”

For Mr. Trump’s allies, lower court judges are the ones who exceeded their authority in blocking presidential actions, interfering with what they claim is a popular mandate. That view was shared by one judge, a Trump appointee, who praised the Supreme Court for “flushing out anti-democratic rulings” with its emergency orders.

The main complaint voiced by a majority of the judges was not where the Supreme Court was coming down, but how it was doing so. By presenting its emergency orders in just a few sentences, with little or no reasoning, judges said the Supreme Court was leaving them without a clear path to assess what the justices were thinking.

The result, one judge said, was that the court was expecting their district court colleagues "to read their minds about what their view of the law is."

Despite the justices' brevity and lack of reasoning, the Supreme Court has become more insistent that its emergency orders are supposed to serve as guideposts for the lower courts. In an unsigned emergency order from July, the Supreme Court noted that while emergency orders were "not conclusive," district court judges should still consider them in "like cases."

Some justices have gone further, using their opinions to publicly admonish judges who, in their view, are failing to correctly apply the court’s emergency orders. In August, Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh took to task Judge William G. Young of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts for what they saw as a failure to apply an emergency ruling in one spending case to another. “Lower court judges may sometimes disagree with this court’s decisions,” the justices wrote, “but they are never free to defy them.”

In response, Judge Young issued a rare apology from the bench, though he expressed some bewilderment with the court’s opacity.

“Never, before this admonition, has any judge in any higher court ever thought to suggest that this court had defied the precedent of a higher court -- that was never my intention,”

he said.

Several judges singled out the justices’ criticism of Judge Young, an 85-year-old appointee of President Ronald Reagan and an Army veteran who has sat for more than 40 years, as a particularly demoralizing breach of decorum.

That view resonated with one of their retired colleagues, Jeremy Fogel, who was a federal judge for 20 years. Judge Young, he said, “has been at it for so long. He’s done the toughest cases, and he’s done them well. For a guy like that to get bench-slapped for not reading the tea leaves properly? That’s just not fair.”

Justice Gorsuch’s opinion could be read as “promoting a disrespect for the judiciary,” one that echoed Mr. Trump’s rhetorical attacks on judges, said Nancy Gertner, a retired judge who teaches at Harvard Law School. Both, she said, “undermine the bench and promote an atmosphere of disrespect.”

The Lower Courts Speak Out

Responses to the questionnaire were overwhelmingly critical of the Supreme Court, but they were not unanimous. Twenty-one judges either declined to answer the question about the effect of emergency orders on the public’s perception of the judiciary or said they believed they have had little or no effect.

A few judges were more equivocal about emergency orders, views that were echoed by Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, a widely respected jurist and Reagan nominee who wrote a robust defense of the role that district courts play in the constitutional scheme. In an interview, Judge Wilkinson noted that the Supreme Court was largely at the mercy of circumstances beyond its control: a high volume of emergency challenges to a presidency that “would put its foot on the pedal because it has an agenda and it’s sensitive to electoral mandates being perishable.”

While noting that the emergency docket had its advantages in terms of quickly and uniformly managing a mushrooming caseload from the executive branch, Judge Wilkinson said there were good arguments for the Supreme Court to be careful about using it too much.

“You don’t want too many snap judgments and emergency orders creating a public impression of either secretiveness or arbitrariness,”

he said.