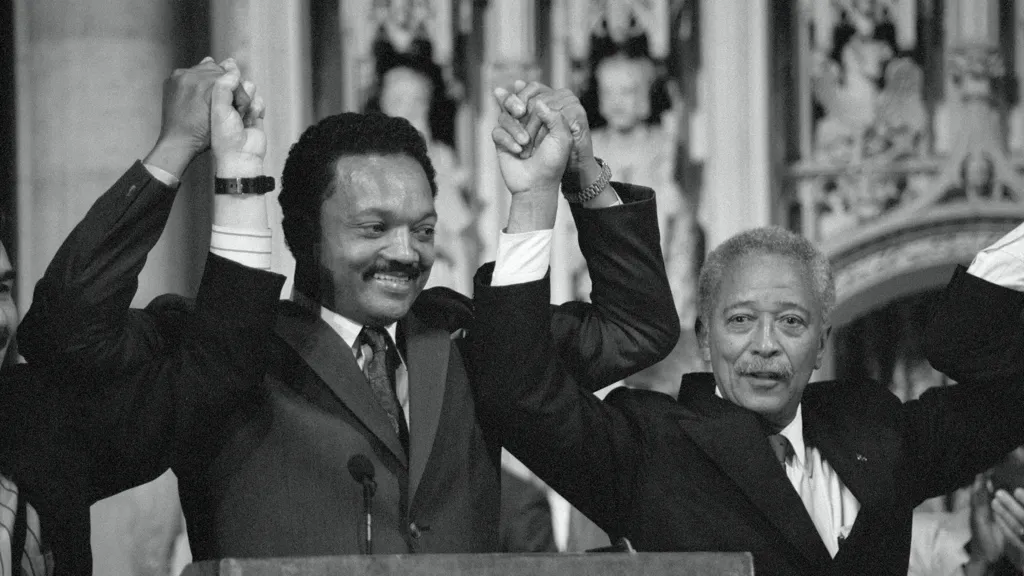

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who died this week, ran for president twice, leading more Black voters to register. The year after his second run, a Black mayor, David Dinkins, won in New York.

Good morning. It's Thursday. Alternate-side parking is back! Today we'll look at how the Rev. Jesse Jackson Jr. influenced politics in New York City, including last year's mayoral race, and we'll also look at Mayor Zohran Mamdani's decision to reinstitute homeless encampment sweeps.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson Jr., who died this week at 84, is best known for his civil rights work in the American South and his deep ties to the city of Chicago.

But over the course of his long career in both politics and activism, Jackson had a lasting impact on the racial and sectarian politics of New York City.

As Peter Applebome writes in his obituary, Jackson's two runs for president in 1984 and 1988 were defined by soaring rhetoric that lifted up a multiracial coalition that had been on the sidelines of American politics and "would now move to the forefront and transform it."

Black men had recently been elected to lead Los Angeles and Chicago -- but not New York City. Jackson's campaigns laid a foundation for a Black politician to win in America's largest city, which was beset by racial tensions and poverty.

A coalition of white liberals -- particularly Jewish ones -- and Black and Latino voters had become a potent force in urban politics at that time. But that partnership was showing signs of fraying, partly because of comments Jackson made while running for president in 1984, when he referred to Jews as "Hymie" and to New York as "Hymietown." He later apologized.

My colleague Jonathan Mahler, who recently published "The Gods of New York," the definitive history of New York City during this period, wrote about those comments this week: "In New York, the word 'Hymietown' hit with particular force, both because of its large Jewish population and because of its fiercely proud Jewish mayor, Ed Koch, who was not only furious about the remark but also about Jackson's ties to the antisemitic leader of the Nation of Islam, the Rev. Louis Farrakhan."

"It was terrible timing for Jackson, but also for the increasingly precarious political alliance between Black people and Jews," Jonathan added, noting that Jackson, to the consternation of some Jewish politicians in the city, was also a vocal defender of Palestinian rights.

Jackson lost the state's primary in 1988 but won New York City, driving record turnout among minority voters. The results emboldened a cadre of advisers for Jackson to encourage David Dinkins, then the Manhattan borough president, to challenge Koch.

"He was very expressive about those two campaigns really cementing Black political power in New York and, quite frankly, across the country," Stacy Lynch, the daughter of one of those advisers, Bill Lynch, said in an interview. She is now a senior political adviser to Gov. Kathy Hochul and recalled handing out fliers as a child for the Jackson campaign. Jackson would sometimes come to her home and cook breakfast for her and her brother while he talked strategy with their father.

Jackson's focus on economic justice and a forgotten underclass set the stage for Mayor Zohran Mamdani's political hero and inspiration, Senator Bernie Sanders. And in Mamdani’s successful campaign themes, you can hear the notes that vaulted Jackson to such prominence.

Dinkins and Mamdani were both democratic socialists who included in their campaigns the message that the city was failing its neediest residents. Their victories showed the potential of a vision of governing that aimed to lift up poorer and nonwhite New Yorkers who had felt ignored by politicians.

Dinkins was initially reluctant to enter the race, and after beating Koch in the primary he avoided Jackson for parts of the general election campaign. Even so, reporters repeatedly questioned him on the topic, and his opponent, Rudy Giuliani, bashed him for his ties to Jackson.

Though Jackson set the stage for Dinkins, the full connection is often obscured by Dinkins’s efforts during that campaign to distance himself from his ally.

Mahler writes in his book that Jackson’s “shadow still loomed large.”

“To many Black New Yorkers, Dinkins’s election felt like the culmination of a battle that had started with Jackson’s 1988 campaign in New York,” Mahler writes. “In a sense, it had started even earlier: It was Jackson’s first presidential candidacy in ’84 that had ignited massive voter drives across Brooklyn enabling strong turnout for Dinkins five years later.”

Weather

A cloudy day is ahead with temperatures near 42. Tonight, there's a chance of rain and snow, with a low around 37.

ALTERNATE-SIDE PARKING

The long suspension, which began on Jan. 26, is over. Parking rules are in effect until March 3 (Purim).

QUOTE OF THE DAY

"I don't want him to be derailed." -- Ronnie Marks, a retired musician, on Mayor Zohran Mamdani's use of his election-winning social media strategy to try to connect City Hall to all New Yorkers.

The latest New York news

- N.Y.C. building homes on land it owns: A police parking lot in East Harlem is being developed into an affordable housing building. It will include nearly 100 apartments for formerly homeless New Yorkers and more than 240 additional affordable units.

- Can Mamdani freeze the rent? Mayor Zohran Mamdani appointed six members to the Rent Guidelines Board, which has the power to freeze the rent in rent-stabilized apartments, making it more likely than ever that he will come through on his campaign promise.

- Manhattan hospital ends medical program: NYU Langone Health, faced with threats of losing federal funding, decided to discontinue its Transgender Youth Health Program.

- What's your unique parking situation? The New York Times wants to hear from New Yorkers who rent driveways or have curious, vexing or surprising parking arrangements.

The debate over encampments

Of the many hot-button topics surrounding New York City's intractable homelessness crisis, few are as divisive as the question of what to do about the encampments that some homeless people erect on sidewalks, under scaffolding and in parks.

Many New Yorkers see the encampments as dirty, dangerous encroachments on public space. The city's previous two mayors cleared them aggressively, sending crews to dismantle campsites and haul off their contents in garbage trucks. Advocates for homeless people, however, say that "sweeps," as they are called, simply shift people from one spot to another, improperly trashing their belongings in the process, without solving the problems that lead them to live on the street.

New York's new mayor, Zohran Mamdani, had spoken out against sweeps, saying, "If you are not connecting homeless New Yorkers to the housing that they so desperately need, then you cannot deem anything you're doing to be a success." A few days after he took office, he stopped them entirely.

But my colleagues Emma Goldberg and Jeffery C. Mays reported on Wednesday that Mr. Mamdani had decided to resume sweeps -- albeit with a difference. Instead of being led by the police and the Sanitation Department, sweeps will be led by the city's Department of Homeless Services. And before an encampment is cleared, outreach workers will visit the site for seven straight days to try to get people into shelter and longer-term housing, City Hall says.

Mr. Mamdani's decision follows the deaths of at least 20 New Yorkers in the recent brutal cold snap, many of them homeless.

Critics of the mayor had warned that letting people remain in encampments rather than forcing them indoors could have fatal consequences. "There is nothing 'progressive' about leaving people to freeze in makeshift encampments," Mr. Mamdani's predecessor, Eric Adams, said back in December.

Mr. Mamdani has said that as far as the city knew, none of those who died were living in encampments. But on Feb. 3, a 74-year-old man who had lived for at least a year in a campsite near the Long Island Expressway in Queens was found dead in the cold. A woman who knew him said that he had been visited by an outreach worker bearing blankets as winter approached.