Mr. Buruma is a professor at Bard College and the author of the forthcoming book "Stay Alive: Berlin, 1939-1945."

To live in Berlin under the Nazis during World War II must have been an extraordinary experience. To be deported to death camps, if one was one of the tens of thousands of Jews who were still alive and living in Berlin, was horrific. For non-Jews, living in a police state was frightening enough. Being bombed day and night in the last two years of the war was surely terrifying.

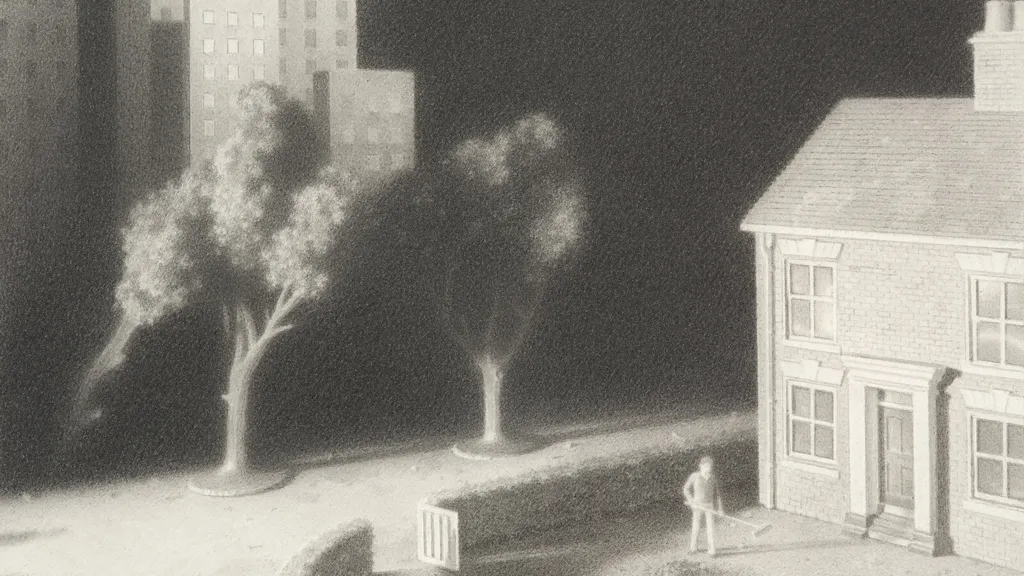

The terrorism of the Nazi state was often in plain view. If you lived in Grunewald, one of the wealthiest parts of Berlin, you could have seen Jews being marched to the railway station, from which freight trains packed with humans left for the ghettos and death camps in Eastern Europe. Others would have seen neighbors dragged from their homes. In some cases, they could have heard the screams of prisoners in the forced labor camps that were spread all over the city.

And yet most people looked away, pretending to see nothing, and carried on with their lives. Why? As is so often the case under autocratic regimes, from Hitler's Berlin to Mussolini's Rome to Vladimir Putin's Moscow, things go from bad to worse in stages. Today's outrage is tomorrow's normal. People adapt and get used to it.

My interest in what happened in Berlin during the war was sparked by my father's letters from the Nazi capital between 1943 and the end of the war. A student in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands, he was deported to Germany as a forced laborer. His life was far from normal. But even as an unwilling foreign worker, he was able to observe the daily life of Germans, who often appeared to be oblivious to the horrors taking place around them.

In a letter to his sister during winter in 1944, when Berlin was being bombed day and night, he describes a concert by the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler, with the audience and the musicians huddled in thick coats under a roof filled with holes from British and American bombshells.

Almost until the last stages of the war, when the Soviet Army conquered Berlin in a devastating battle that reduced the city to rubble, the cinemas were full; the dance revues were in full swing; the soccer competition went on; and people visited the zoo and sunbathed on the Wannsee opposite the infamous villa where the logistics of the Holocaust were worked out over glasses of brandy.

One reason for public docility in terrible circumstances is fear. In the last years of the war, a Berliner could be arrested and, often, executed for doubting the final German victory -- for defeatism. But there is something more insidious, something not unfamiliar to many of us today: the hope that things will turn out all right soon, that the political outrages are temporary or at least that they can't get worse. One way of dealing with bad times is to pretend that they are normal.

This is the problem when the destruction of moral norms and the rule of law is incremental. Germans should have known that politics would take a criminal turn as soon as Hitler and his brutal paladins grabbed total state power in August 1934. The racial laws of 1935 robbed Jews of their civil rights. But Jews made up less than 1 percent of the German population. So most people could live with the racial laws. In 1938, Hitler annexed Austria and grabbed a chunk of Czechoslovakia. OK. Perhaps that would satisfy the Führer's imperial lust. He surely wouldn't go any further.

By September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, it was clearly too late for normal life to resume. But even then, many Germans believed that Britain and France would not resist. Surely, the war would soon be over. Erich Alenfeld, a Jewish banker married to a Gentile wife, wrote a letter to Goering asking to serve in the invading army. After all, he was still a German patriot. He never received an answer.

And so life continued. People kept hoping that the next act of war and assault on decency would be the final one and the nightmare would finally end. Even in 1945, when terrifying Soviet artillery was within earshot and much of Berlin lay in ruins, there was still hope that wonder weapons -- fearsome missiles that would destroy and demoralize London or machines that would pull Allied bombers from the skies like giant magnets -- would turn things around.

The human capacity for hope is an essential quality. Without hope, there can be no improvement. But hope can also turn into delusion. The United States today is not Hitler's Third Reich. We are nowhere near the disastrous circumstances of Berliners in 1945, 1939, 1935 or even 1934. But as humans, we are prey to similar kinds of self-deception.

When Donald Trump refused to say whether he would accept the outcome of the election in 2016, people should have sensed the danger. And yet at the time, respected intellectuals told me that everything would be fine: All he wanted was to play golf or make money. Anyway, Hillary Clinton and George W. Bush were worse, for they condoned or unleashed unnecessary wars. I was told by a well-known American historian that there was really nothing to worry about, for after all, Roosevelt once had authoritarian tendencies, too. Democracy would never be shattered, a law professor assured me, for "Americans love freedom too much."

Since then, one red line after another has been crossed: Undocumented immigrants are called animals; civilian boats are blown out of the water; American citizens are gunned down in the streets and then accused of being domestic terrorists; universities, news organizations and law firms are being bullied and blackmailed; and refugees are deported to countries whose languages they probably don't even speak. And that is aside from the blatant corruption of family and cronies.

All this was incremental too but compared with 1934 everything goes much faster. And yet life continues as usual. What was unthinkable only yesterday we now take in stride and we wait for that moment when things really have gone too far this time when the fever breaks and things will revert to normal.

But that moment probably won't come. Things have gone too far too many times already. Hoping for better is still the right attitude but only as long as we prepare for the worst.

Ian Buruma is the author of "The Collaborators" and other books.