Adam Harrington is a digital producer at CBS Chicago, where he first arrived in January 2006.

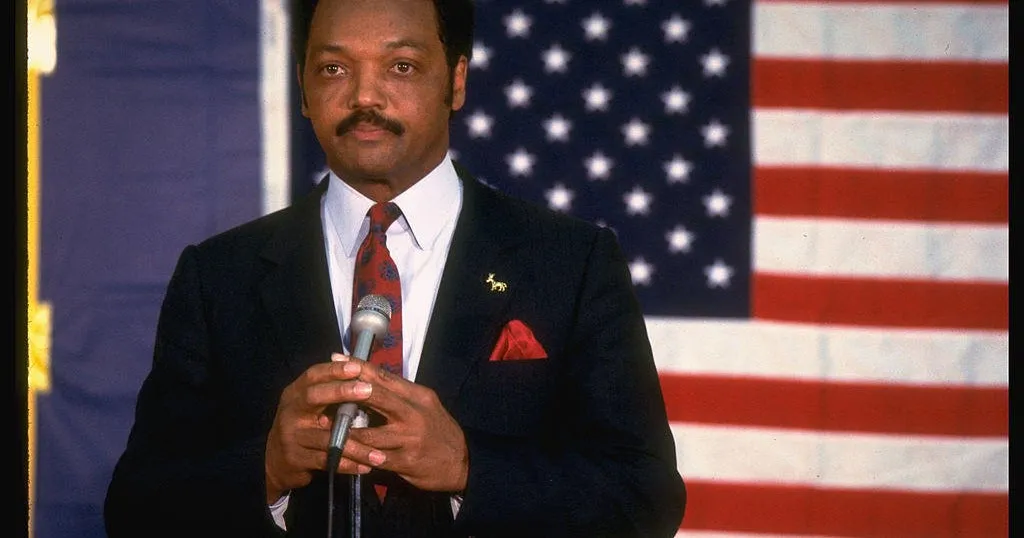

The Rev. Jesse Jackson's life was tied tightly to the city of Chicago and its people going back to when he first arrived in the city as a theological student in 1964.

Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina in 1941. He received a scholarship to enroll in college at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign in 1959, but transferred to North Carolina Agricultural & Technical College two years later.

In 1964, Jackson moved to Chicago on a Rockefeller grant to study at Chicago Theological Seminary. The following year, he and a group of students drove from Chicago to Selma, Alabama, to join Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to campaign for voting rights, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

While in Selma, Jackson asked SCLC cofounder Ralph Abernathy for a with SCLC to lay the groundwork for Dr. King's Chicago Freedom Movement -- which brought the fight for Civil Rights from the South to northern cities.

Jackson was hired on the spot, and Dr. King joined him in Chicago in January 1966. Jackson dropped out of seminary to help Dr. King full-time and became head of SCLC's Operation Breadbasket in Chicago. Operation Breadbasket was an economic program to promote employment for Black people and take action against businesses that discriminated.

The institute at Stanford noted that under Jackson's leadership, Operation Breadbasket in Chicago targeted five dairy businesses, demanding they hire more Black employees. Three complied immediately, but two only complied after boycotts, the institute said.

Under Jackson, Operation Breadbasket in Chicago went on to target Pepsi and Coca-Cola bottlers and supermarket chains, the institute said. The program won 2,000 new jobs with $15 million a year in new income for Chicago's Black community in its first 15 months, the institute said.

In January 1967, Dr. King called Operation Breadbasket SCLC's "most spectacularly successful program" in Chicago, the institute said. Of Jackson's leadership, Dr. King said, "We knew he was going to do a good job, but he's done better than a good job."

That same year, Jackson was promoted to national leadership of Operation Breadbasket, with King telling an audience in Chicago on Jan. 6, 1968, that "no one would be "more effective in the role," the institute said.

But Jackson also clashed with Dr. King, who criticized Jackson for following his own agenda instead of supporting the group, the institute said. They reconciled after King called Jackson and asked him to join him in Memphis, where Jackson was talking with King from below the balcony of the Lorraine Motel when King was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

Jackson went on running Operation Breadbasket until 1971, when he left the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and founded Operation PUSH -- short for People United to Save (later Serve) Humanity. The Chicago-based Operation PUSH focused on improving the economic conditions for Black communities across the country.

The New York Times covered Jackson's announcement of the founding of Operation PUSH before an enthusiastic crowd in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood.

"Wearing a blue vest and checkered shirt, Mr. Jackson conducted a spirited four‐hour meeting at the crowded Metropolitan Theater on Dr. Martin Luther King Drive, near 47th Street," the Times reported on Dec. 18, 1971. "People sat in the aisles, lined the walls and made the sidewalk outside impassable."

As quoted by the New York Times, Jackson told the crowd: "We must picket, boycott, march, vote and, when necessary, engage in civil disobedience.... We must express our power -- the courts are too slow -- the judges are too corrupt."

Throughout the 1970s, Operation PUSH expanded its reach with direct action campaigns, a weekly radio broadcast, and awards, according to its successor organization. Operation PUSH also launched PUSH Excel, which worked to keep inner-city young people in school while helping them with job placement. PUSH also worked to demand that major corporations hire more Black executives and managers, and used prayer vigils and boycotts to ensure the demands were met.

In 1972, Jackson and Chicago Ald. William Singer led a successful campaign to unseat Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley's slate of delegates at the Democratic National Convention in Miami.

In 1982, Jackson led a boycott of ChicagoFest, the annual summer food and entertainment festival held at Navy Pier. This came after Mayor Jane Byrne nominated three white board members to new positions on the board of the Chicago Housing Authority -- creating a white majority on the board for the organization. At the time, the CHA was the target of criticism for the conditions in its housing projects, where Black Chicagoans predominantly resided.

Stevie Wonder, a supporter of Operation PUSH, called off his plans to appear as a headliner at ChicagoFest that year.

In 1983, Jackson rallied support for Harold Washington to be elected as Chicago's first Black mayor.

"Dr. King did not march in vain," Jackson said in campaigning for Washington. "This is our day."

Jackson launched a second organization, the National Rainbow Coalition, after an unsuccessful run for the presidency in 1984.

From October 1985 until August 1986, CBS Chicago was the target of a boycott by Rev. Jackson and Operation PUSH after Harry Porterfield, the station’s only regular Black anchor, was pulled from the weekday anchor desk and went on to leave the station. The boycott spread to other CBS-owned stations and ended with a settlement acknowledging an increase in the hiring of minorities and women at Chicago’s Channel 2.

Jackson and Operation PUSH also took credit as Johnathan Rodgers, appointed during the boycott as WBBM-TV’s first Black general manager, hired a new Black anchor, Lester Holt.

After another unsuccessful run for president, Jackson moved to Washington, D.C., in 1989.

In December 1995, Jackson’s son, Jesse Jackson Jr., was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in a special election. The younger Jackson would serve until November 2012, when he resigned his seat and went on to plead guilty to misuse of campaign funds. In 2025, Jackson Jr. announced he was running to take back his old seat.

The Rev. Jackson moved back to Chicago in 1996 and merged the Operation PUSH and the National Rainbow Coalition into the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition -- headquartered at 930 E. 50th St. in the Kenwood neighborhood.

Whie Jackson was ordained as a minister in 1968, he had never received his degree from the Chicago Theological Seminary, located adjacent to the University of Chicago in Hyde Park. That changed in 2000, when Jackson was awarded his Master of Divinity from the institution.

In 2008, Jackson wept as Barack Obama gave a victory speech before a cheering crowd in Grant Park upon being elected president.

Jackson went on making headlines throughout the 2010s for his activist work in Chicago. In 2012, he spent the night at Pacific Garden Mission for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day to draw attention homelessness. That same year, he worked unofficial mediator during heated Chicago teachers' strike.

In October 2014, Chicago police Officer Jason Van Dyke shot 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times and killed him, but video of shooting was not released until November 2015 after legal action. Jackson led protest downtown Chicago December 2015 against what he called cover-up police shooting.

Another of Jackson's sons, Jonathan Jackson, was elected Congress 2022.

Jackson stepped down president Rainbow/PUSH Coalition July 2023, four yeas after he was diagnosed Parkinson's disease. He received honors numerous events subsequently, including celebration Rainbow/PUSH Headquarters eve Democratic National Convention 2024.