Most teenagers know that baseless conspiracy theories, partisan propaganda and artificially generated deepfakes lurk on social media. Valerie Ziegler's students know how to spot them.

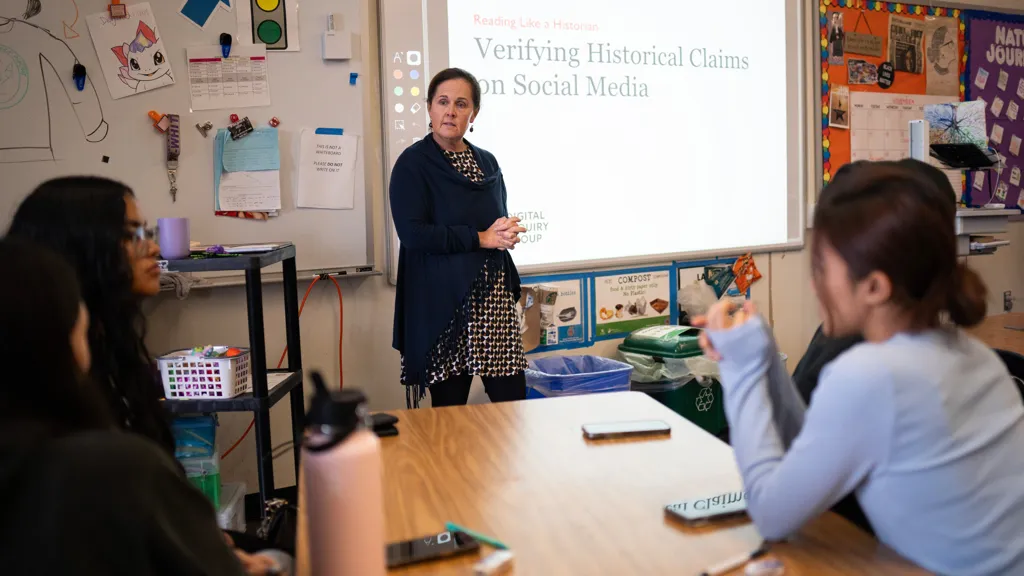

At Abraham Lincoln High School in San Francisco, she trains her government, economy and history students to consult a variety of sources, recognize rage-baiting content and consider influencers' motivations. They brainstorm ways to distinguish deepfakes from real footage.

Ms. Ziegler, 50, is part of a vanguard of California educators racing to prepare students in a rapidly changing online world. Content moderation policies have withered at many social media platforms, making it easier to lie and harder to trust. Artificial intelligence is evolving so quickly and generating such persuasive content that even professionals who specialize in detecting its presence are being stumped.

California is ahead of many other states in pushing schools to teach digital literacy, but even there, education officials are not expected to set specific standards until later in 2026. So Ms. Ziegler and a growing group of her peers are forging ahead, cobbling together lesson plans from nonprofit groups and updating older coursework to address new technologies, such as the artificial intelligence that powers video apps like Sora. Their methods are hands-on, including classroom exercises that fact-check posts about history on TikTok and explore how badges that appear to signal verification on social media can often be bought rather than earned.

Teachers and librarians around the country have long tried to prepare students for the pitfalls of being online, but the past few years have underscored for educators just how much of their work increasingly involves playing catch-up with a moving target.

Ms. Ziegler's efforts showcase the difficulties of keeping pace with new social media platforms, apps and advances in A.I.

"We're sending these kids out into the world, and we're supposed to have provided them skills," Ms. Ziegler, a former California teacher of the year, said. "The tricky part is that we adults are learning this skill at the same time the kids are."

Social media literacy is a tough subject for schools to try to teach, especially now. Federal funding for education is precarious, and the Trump administration has politicized and penalized the study of disinformation and misinformation. A.I. is becoming pervasive in the educational system, available to younger and younger children, even as its dangers to students and educators become increasingly clear.

The News Literacy Project, a media education nonprofit, surveyed 1,110 teenagers in May last year and found that four in 10 said they had any media literacy instruction in class that year. Eight in 10 said they had come across a conspiracy theory on social media -- including false claims that the 2020 election was rigged -- and many said they were inclined to believe at least one of the narratives.

Ms. Ziegler teaches the self-described "screenagers" in her classes that their social media feeds are populated using highly responsive algorithms, and that large followings do not make accounts trustworthy. In one case, the students learned to distinguish between a reputable historians group on Instagram and a historical satire account with a similar name. Now, they default to double-checking information that interests them online.

"That's the starting point," said Xavier Malizia, 17.

Ms. Ziegler first tried to teach A.I. literacy last year by testing out a new module from the Digital Inquiry Group, a nonprofit literacy organization. She relies heavily on collaborations, often consulting with her school's librarian or using free resources from CRAFT, an A.I. literacy project from Stanford University.

Riley Huang, 17, said she had recently been nearly, but not quite, duped by artificially generated clips that portrayed Jake Paul, a popular boxer and influencer, as a gay man applying cosmetics. Elisha Tuerk-Levy, 18, said it was "jarring" to watch a realistic A.I. video of someone falling off Mount Everest, but added that the visuals in such videos were often too smooth -- a useful "tell" that helps identify them as fake.

Zion Sharpe, 17, noted that A.I.-generated videos often seem to originate from accounts where all the posts feature the same person wearing the same clothes and speaking in the same intonation and cadence.

"It's kind of scary, because we still have a lot more to see," Zion said. "I feel like this is just the beginning."

Policymakers are paying more attention to the issue. Dr. Vivek Murthy, the surgeon general under President Joseph R. Biden Jr., urged schools in 2023 to set up digital literacy instruction. At least 25 states have approved related legislation, according to an upcoming report from Media Literacy Now, a nonprofit group. This summer, for example, North Carolina passed a law requiring social media literacy coursework starting in the 2026-27 school year, covering topics such as mental health, misinformation and cyberbullying.

Many of those new rules, however, are voluntary, toothless or slow to take effect or do not acknowledge the growing presence of artificial intelligence.

"I absolutely wish we could make things happen faster," said Assemblyman Marc Berman of California, a Democrat who wrote two media literacy bills passed in 2023 and 2024. The bills nudged the state to incorporate lessons about media literacy and responsible A.I. use at each grade level, but California education officials have yet to decide on a formal course of action.

"It's about really strengthening those foundational skills so that no matter what tech pops up between now and then, young people have the ability to handle it," Mr. Berman said.

Ms. Ziegler and her peers across California and the country are scrambling to make sense of A.I. The San Diego Unified School District held A.I. expos for its teachers over the past two summers, with each drawing more than 150 educators. At the Elk Grove Unified School District in Sacramento County, teachers have turned to Code.org, MIT Media Lab and others for resources focused on A.I.

Educators are grappling with A.I. literacy even beyond high school. Augsburg University in Minneapolis offered a class this year called "Defense Against the Dark Arts," focused on how "disinformation, alternate facts, propaganda, deepfakes" and more saturate social media and daily life. Adam Berinsky, a political science professor at M.I.T., has taught a class about misinformation on social media since 2019 but added lessons on the challenges and benefits of A.I. in the spring.

"A.I. is everywhere these days," he said. "I adjusted teaching accordingly."

Ms. Ziegler's students are a savvy bunch, though the volume of junk online can feel overwhelming.

In November, her classes chatted about the flood of social media content featuring Zohran Mamdani, the first Muslim to be elected New York City's mayor. During the election, authority figures once considered trustworthy sources -- including a sitting member of Congress and the former governor of New York running against Mr. Mamdani -- shared artificially generated content showing the Statue of Liberty wearing a burqa and Mr. Mamdani being praised by criminals. (The latter included a small, brief disclosure that it was generated by A.I.) Posts spreading disinformation about his policy plans received hundreds of thousands of views, dwarfing those of fact-check posts.

At one point in the discussion, a student piped up with a common refrain: "Don't trust anything you see."

That sentiment worries Ms. Ziegler. Fact-checkers and disinformation analysts have cautioned for years about a creeping sense of nihilism toward reality.

"There's almost this mind-set now with young people that everything's fake," she said. "They have heard so much about things being fake online but they don't know how to necessarily tell."