Australia is invited to step into a quiet room and watch the truth of its history emerge from the darkness.

The history of this land is marked by violent milestones. Indigenous Australians have suffered at the hands of colonisers in countless ways since European invasion 237 years ago. The stories continue to echo from one generation to the next. Yet this short history must be understood within the vast context of 65,000 years of culture and the strength of First Nations peoples.

A new exhibition by the Bigambul/Kamilaroi artist Archie Moore, curated by Ellie Buttrose, shares some of these stories at ambitious scale. The multimodal artwork stunned and enraptured audiences at the 2025 Venice Biennale, becoming the first Australian work to win a coveted Golden Lion. Now, it can be seen on Australian shores for the first time at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane.

Buttrose has known Moore for more than 15 years. Having worked with him previously—and seen the impact of his art—she knew that the monumental kith and kin would be worth the epic process required to install it.

"With something of this scale," she says, "it's about bringing people together that have the skills that can enable Archie's vision to come to life. His artworks create a mood in the space, which means that every element of the design must contribute to the feeling that he evokes.

"We worked together with design consultant [and Kaurareg-Meriam man] Kevin O'Brien to plan the various elements in the artwork. Changes in distance and height and light emphasise different parts of the artwork, and change the meaning of the piece. We needed to play out all the different scenarios to know that we have the right one, and the result is very close to what Archie had first envisioned."

Moore says both the Venetian and Australian installations have drawn on local experts to make the mammoth task possible. "It's two months' hard labour, on a much larger scale than we ever worked on before, and with a much larger team," he says. "That was all new to me."

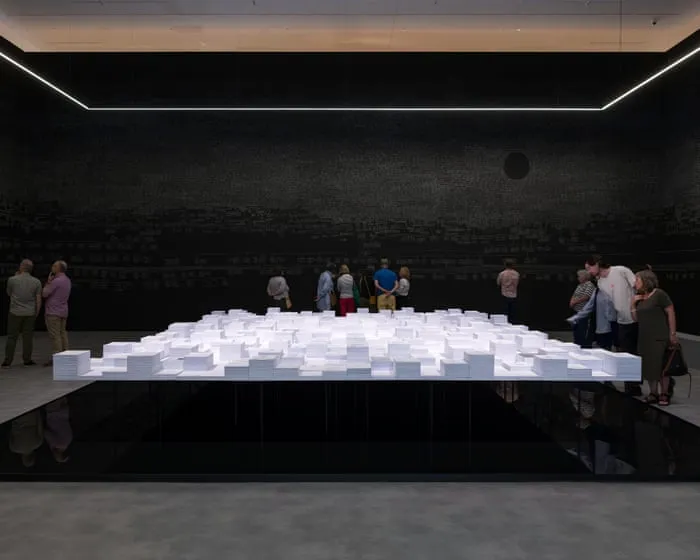

Visitors to kith and kin are forced to take a moment to let their eyes adjust. As the minutes pass, a massive artwork is revealed through the darkness: coronial reports suspended over a memorial pool, backdropped by thousands of names chalked on blackboard walls. This is Moore's history of kinship, connection and time, tracing pathways to common ancestors of all humans alongside animals, plants, waterways and landforms.

In this space, 65,000 years of Indigenous ancestry is contrasted against atrocities still occurring in the present day. In keeping with Moore's artistic practice, it positions personal experience in the wider political landscape, challenging those who view it to consider their kinship responsibilities to one another and the wider world.

"The whole piece is about connections," Moore says. "It's a place for reflection and contemplation, as in a shrine or memorial. I noticed people slow down in there to walk around."

Within the QAGOMA exhibit, a window opens to the sky. At the Australia Pavilion in Venice, there was a window through which you could see a canal. "The water in the canal is a way to connect us all, just like the sky does," Moore says.

That water flows to the Venetian Lagoon, to the Adriatic Sea, and around the world to the Brisbane River, where QAGOMA stands.

"We have common ancestors," Moore says. "We're all part of a much larger family and we have a responsibility to treat each other with kindness and respect. Everyone has a family, so everyone can relate to the tree and genealogy."

This is not Moore's first piece about violence against Indigenous peoples, and unlikely to be his last. "This death in custody problem is still happening," he says, "even though there are 339 recommendations to solve the problem. There's an unwillingness to make it happen."

The memorial pool at its centre literally reflects the meaning of the work to visitors. "At certain angles, you'll see the tree being reflected in the water," Moore says. "It's in close proximity with death in custody reports, bringing those two elements together to talk about how the people in the reports are human beings. They have families. They're not just a statistic."

Moore's use of chalk and blackboard speaks directly to the issue. "When I have an idea for a work, I'll have a think about what media best suits that idea. I've used perfumes, paper, sculptures, paint. This work is chalk and blackboard, to reference the school curriculum that I studied under - there was no Indigenous history or Indigenous references in any of the subjects. It is a history painting.

"The chalk is very fragile; could be smudged easily; so most people are really careful in there. But if you wanted to try and erase it, I think there’d always be a trace left behind. This erasure of histories; the erasure itself becomes a part of history."

Moore and Buttrose hope the global recognition that came with winning a Golden Lion will encourage more people to visit the work and reflect on its message.

Buttrose says: "It shows you what can happen when Australian artists are given significant resources at the right time in their career. We hope that the praise for kith and kin leads to more challenging projects at scale, not just by Archie but other Australian artists. The resonance that it's had with an international audience—the fact that people considered it one of the most important artworks of its time—means that yes we should continue to support and be very proud of what artists here in Australia are able to create and deliver."

Moore says it's been "amazing" to be honoured with the prestigious award. "It was great to be recognised and acknowledged for the work which we thought was really good work," he says. "We believed in it."