Since 2021, the Eastern Kentucky Remembrance Project have planted markers memorializing Black residents killed by racist violence.

On 26 October 1924, Fred Shannon, a Black man, was lynched at age 28 by a mob of nearly 200 masked residents in Wayland, Kentucky.

Shannon, a local musician, was falsely accused of killing a white man over a financial dispute. While was he being held at a local jail, the mob broke in, took him out in the street and shot him at least 18 times.

For decades, Shannon's lynching and the murders of other Black men in the region went largely unnoticed, lost to history. But over the past four years the Eastern Kentucky Remembrance Project (EKRP), an interracial, intergenerational coalition of residents, has come together to memorialize their lives - and deaths. In May, the group successfully placed a remembrance marker for Shannon. EKRP managed to find a relative of Shannon, who will visit the site within the year. Research is already underway for more markers to honor those who were lynched in eastern Kentucky, carrying on the years-long tradition.

Founded in 2021, the EKRP has worked to honor Black people who were lynched in the region with plaques and other markers. The group also cleans up a Black cemetery in the area as a part of its annual Decoration Day celebration.

The project was first started during a Zoom meeting for the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth Group, EKRP's parent organization. John and Jean Rosenberg, who founded the EKRP, had visited the Legacy Museum, run by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), based in Montgomery, Alabama, and learned of Shannon's lynching in Floyd county. The pair wanted to acknowledge the travesties that had taken place, according to members in the meeting. "It's important for us to face this history," said John in a 2021 press release about the group's founding.

Five years later, Shannon's memorial service took place.

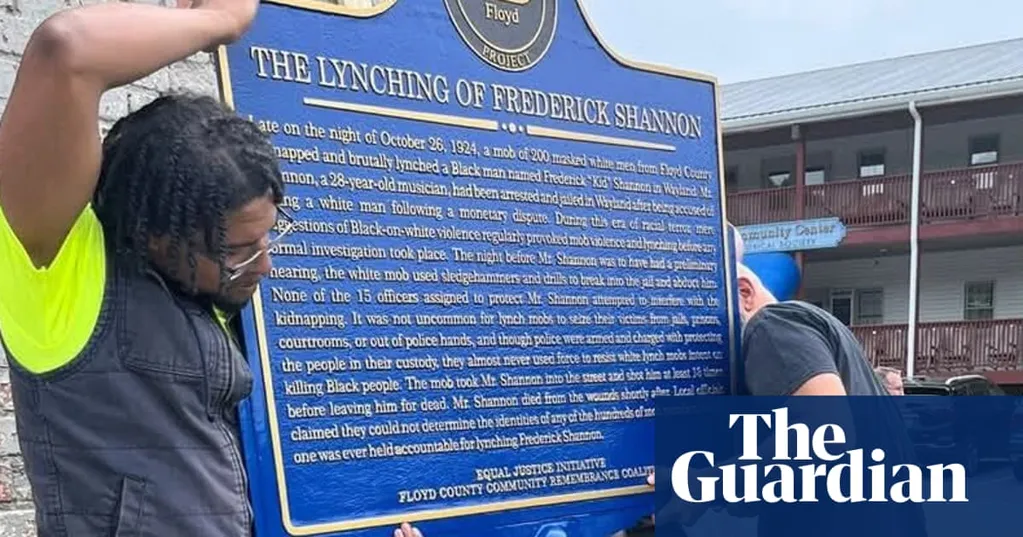

On 31 May, a historical marker provided by grants from the EJI was placed outside the former Wayland jail where Shannon was killed, now a neighborhood liquor store. Dirt from the site was collected for the EJI's Community Remembrance Project, which houses soil from various lynching sites across the country.

Darryl "Dee" Parker, an EKR member, participated in the ceremony, calling it "bittersweet" to memorialize Shannon while also recognizing the immense violence done to him. "It was just something about touching the soil," Parker said, who is Black. "Just started having this little flashback,[thinking how] Fred's blood is in the soil somewhere."

Parker, like many participants in the project, have personal connections to lynching that took place in the area. During a visit to EJI, Parker learned that several of his own family members had been lynched in Kentucky. Tom Brown, a male relative, had been lynched in Nicholasville, Kentucky, after being accused of speaking to a white woman. Another family member was lynched in Midway, Kentucky; Parker’s family believes that he was working at a local distillery and was accused of stealing liquor. His grandmother later confirmed the news, figuring that Parker had already known. “Nobody really talked about this in the family. If I didn’t uncover that, then that would have been lost because I wouldn’t be able to tell my kids and grandkids and so forth,” Parker said.

Beverly May, member of EKR and longtime eastern Kentucky resident, also has personal ties to Shannon’s killing. May, who was on the initial Zoom call that sparked EKR’s creation, was “stunned” to learn about Shannon’s lynching in the region. “I was really horrified that the lynching, something that I thought just happened in the south, happened a few miles from my house.”

Wayland’s own mayor hadn’t known Shannon’s killing was a lynching, assuming that it was punishment for murder. May soon learned she had a connection to Shannon’s lynching; she discovered that her great-grandfather was sheriff of the county when Shannon’s murder occurred. During a family reunion in 2022, May asked her relatives if they had heard anything about Shannon’s lynching, especially as hundreds of men had participated. “They all shook their heads and said: ‘No,'” said May, who is white. “I don’t know if they told me the truth or not, but I know that there was no further discussion except, ‘No, I didn’t know that,’” May added.

The work remains as relevant as ever, said EKR members, especially as the Trump administration continues to attack the teaching and archiving of Black history. Trump has also pledged to bring back statues commemorating Confederate leaders, many of which were successfully removed during 2020.

A handful of residents in eastern Kentucky have been unsupportive of EKRP’s efforts, said Parker. “Some people in the town were like, ‘What about the white man who got killed? What about this? What about that?’” he said.

But the majority of people have been in favor of EKRP’s mission and unaware of such violence taking place in the community. “There’s other people that didn’t even know this history at all. [They were] like, ‘Thank you. I’m glad you all are doing this.’” The stone marker even got a “blessing” from the liquor store owner, a quiet man named Bobby who gave EKRP full permission to memorialize Shannon on his land,” said Parker.

The memorial was another form of resistance, especially as racial justice progress nationwide swings backward. “I have been in mourning since the election,” said May. “I am more shocked by the depth and the comprehensiveness of the move toward autocracy, blatant racism and blatant misogyny.”

She added: “[But] the Trump administration has no say so about it. It’s these little steps of remembrance and reconciliation are more important than ever and will continue to be.”