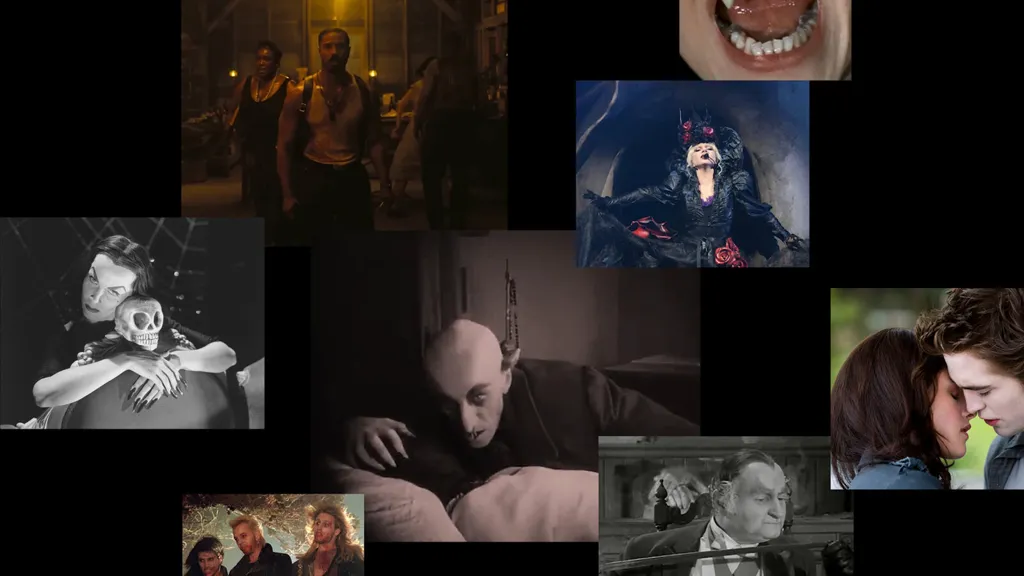

Ever since Bram Stoker's Gothic novel "Dracula" was published in 1897, upending horror like a bat out of hell, the vampire has been a "dramatically generational" survivor, Nina Auerbach wrote in her seminal 1995 book, "Our Vampires, Ourselves."

In a cultural landscape teeming with them, it's no wonder that artists as different as Bela Lugosi and Ryan Coogler have been drawn to vampires like fangs to necks. These mythological creatures tap into our anxiety over what would happen if we became otherly human, even if, like the bloodsuckers on "The Munsters," they seem like nice enough neighbors. As the horror author Grady Hendrix put it: "Vampires are the only monster that looks like us."

So, maybe, it shouldn't be surprising that theater has a stake in vampires this spring. Cynthia Erivo is starring in a one-woman "Dracula" in the West End, and "The Lost Boys," a new Broadway musical based on Joel Schumacher's 1987 supernatural thriller, begins performances on March 27 at the Palace Theater. (Also in New York: "Blood/Love," a vampire pop opera running Off Broadway.)

Michael Arden, the director of "The Lost Boys," said vampires are an enduring pop culture obsession because they force us mortals to consider a deeply seductive what-if: "Is it better to live a never-ending life or is the meaning of life predicated on its brevity?"

How did vampires sink their teeth so deeply into pop culture's flesh? It comes down to blood, and types.

Evil

True Bloodsuckers

The most thrilling vampires are the ones beyond salvation, whose thirsts are primal. No vampire captured this more than Count Orlok, the leading rat-faced ugly in F.W. Murnau's silent masterpiece, "Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror" (1922). Orlok was ruthless and remorseless, and as played by Max Schreck, set a high bar for vampires to come. Filmmakers keep revisiting it, including Werner Herzog, whose 1979 remake, "Nosferatu the Vampyre," featured a ghastly-looking Klaus Kinski, and Robert Eggers, who gave us Bill Skarsgard as a gruesome hulk in his 2024 take, "Nosferatu."

Less beastly but still fiendish was Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning's "Dracula" (1931). Stylistically, Lugosi’s cape-draped bloodsucker was a huge inspiration for future pop vampirism, from Bauhaus’s 1979 Goth anthem “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” to Count von Count on “Sesame Street” and Count Chocula cereal.

The 1979 CBS mini-series “Salem’s Lot” scarred Gen X with nerve-rattling bedroom sequences featuring grinning, hollow-eyed vampires scratching at windows. No wonder these stranger-danger vampires slayed: The series was based on the Stephen King novel and was directed by Tobe Hooper, who forever changed horror with “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.”

Vampires come in all sizes, like Eli, the unmerciful creature trapped in a 12-year-old’s body who made “Let the Right One In” (2008) such a barbaric love story.

Thirst Traps

Evil sophistication makes the vampire a “dream antagonist,” said Stephen Graham Jones, the author of the 2025 vampire novel “The Buffalo Hunter Hunter.”

“The vampire can be both an animal, fighting tooth and claw, but it can sit back and have a very measured conversation with its prey too,” he said.

The vampire sophisticate was the actor Christopher Lee, whose “noble, ravenous” Dracula “exuded a certain lascivious sex appeal,” as this newspaper put it, in films for the U.K.-based Hammer Studios from 1958 to 1973.

Another charmer: Frank Langella, who starred on Broadway in the hit 1977 production of “Dracula” and two years later in the critically acclaimed film adaptation. (You can’t miss the ravenous look Langella’s Dracula gets when his butler accidentally cuts his finger.)

The modern vampire oozes sex more brazenly than its predecessors without always necessarily being coercive. Say what you will about the divisive 1994 film adaptation of Anne Rice’s best-selling novel “Interview With the Vampire,” but Brad Pitt made a comely Louis opposite Tom Cruise’s Lestat. So did Jacob Anderson, who plays Louis as a debonair gay man in the 2022 adaptation of “Interview With the Vampire.” And who wouldn’t want to live forever looking as come-hither as Alexander Skarsgard’s Eric on “True Blood”?

Lady vampires too. Salma Hayek’s snake dance in Robert Rodriguez’s testosterone-fueled “From Dusk Till Dawn” (1996) is one of horror’s most scintillating five minutes. Unlike earlier female vampires, her character, Santanico Pandemonium, wasn’t a passive piece of cheesecake: Her supernatural power made men her minions.

Vampire chic -- body-hugging black leather, floor-sweeping silhouettes -- has long heated the runways at Viktor & Rolf and other houses, delivering aspirational, dark-sided allure. If fashion has a vampire muse it's Lady Gaga, who served bloodsucker eleganza in black corseted Vivienne Westwood at last year's Grammys.

But nobody sold va-va-voom like Vampira (born Maila Nurmi), a 1950s television horror host. Inspired in part by the evil queen from Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” Nurmi’s fitted black gowns and back-grazing locks influenced generations of villainous vixens from Morticia Addams to Elvira.

Queerness

Shadow Dwellers

For many vampires, prey is about blood, not gender -- an "equal-opportunity approach to bloodsucking" that's very queer, according to film scholar Payton McCarty-Simas.

One of the earliest queer-coded vampires was Jonathan Frid’s dapper Barnabas Collins on ABC’s supernatural soap opera “Dark Shadows” (1966-1971). Horror historian Jeff Thompson recalled that Barnabas’s power was in how he connected with young people who may not have even known what “homosexual” meant but knew that they were, like Barnabas, different.

“When they watched Barnabas struggle with his strange desires, gay youth took notice,” Thompson said.

Queer vampires were not just men -- not always a source of pride considering that queer female vampires have often been portrayed as purely predatory. “Dracula’s Daughter” (1936) warned of predatory queer vampirism; a warped take that drove “The Vampire Lovers” and other lurid lesbian vampire films of the 1970s.

Bisexuals—a long neglected group in cinema—fared somewhat better when Catherine Deneuve, Susan Sarandon and David Bowie’s characters brooked the chicest vampire love triangle in “The Hunger” (1983).

WARRIORS

High Stakes

In the second half of the 20th century, vampires became less of a male-predator monolith as they became "carriers of social anxieties and metaphors for the things we fear or are told to fear," as horror scholar Leah Richards put it.

Because of their immortal love for mortal flesh, vampires are often the agents—and victims—of star-crossed, forbidden romance, as was the case with Buffy and Angel in the series "Buffy the Vampire Slayer." More metaphorically, suppressed desires and teenage wanting were the lusts that made the "Twilight" films throb.

Black vampires were at the forefront of the tragically misunderstood vampire. In the Blaxploitation film "Blacula" (1972), William Marshall's title vampire littered Los Angeles with carnage as he sought to reunite with his wife. Wesley Snipes's half-vampire vampire hunter righted wrongs in "Blade" (1998).

Not all battles are winnable. A prevalent metaphor in vampire myths is addiction, which Bill Gunn tackled over 50 years ago in "Ganja & Hess," his maverick treatise on African-American identity. Addiction has since fueled some of horror's most emotionally brutal vampire films, including "The Addiction" (1995) and "My Heart Can't Beat Unless You Tell It To" (2020).

In the 1980s, vampires mirrored widespread anxieties around AIDS—of blood-borne illness but also as a way to process the “inescapable reality of death at an early age,” as film scholar David J. Skal put it in his book “The Monster Show.” Two examples from 1985: Ping Chong’s play “Nosferatu,” set during the dawn of the crisis, and Kathryn Bigelow’s vampire Western “Near Dark,” as an allegory to the American response to AIDS.

Props to vampire killers too, especially the Black heroes of “Sinners,” Ryan Coogler’s rhapsody on race and vampirism that’s up for a record-breaking 16 Oscars.

humor

Fangs a Lot

No joke: Vampires have been hilarious since at least 1948 when Lugosi parodied his own “Dracula” in “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.” That’s what horror comedy does cathartically: Make fright look like no biggie.

Gag vampires gagged audiences at the art house in “The Fearless Vampire Killers” (1967), Roman Polanski’s slapsticky sendup of Hammer horror, and at the grindhouse in “Dracula: The Dirty Old Man” (1969), a sexploitation romp about a vampire with the voice of a Borscht Belt comedian. The horseplay tradition lives on: Adam Sherman’s action-comedy “Vampires of the Velvet Lounge,” with Mena Suvari, arrives in theaters on March 20.

Goofball vampires have also haunted the small screen most recently on “What We Do in the Shadows,” the Emmy Award-winning mockumentary series about lovably dimwitted vampire housemates.

Cutie-pie vampires teach kids that monsters aren’t always enemies. The 1960s sitcom “The Munsters” taught Eisenhower-era squares that an unorthodox family with a vampire mom and grandfather can be as loving as the Cleavers. In the animated “Hotel Transylvania” films, the TikTok generation learned that dads who act tough are sometimes softies.

It’s the Broadway musical where the vampire’s curse is perhaps the funniest unintentionally. Theater has had a notoriously difficult time nailing horror onstage, and vampires have had the worst luck in clunkers like “Dance of the Vampires” (2002) and “Lestat” (2006).

Arden is hopeful that “The Lost Boys” will reverse the musical vampire’s misfortunes.

“It’s not Victorian lace and candelabras,” he said of the show. “It’s squirt guns filled with holy water and kids dressed up like Rambo.”