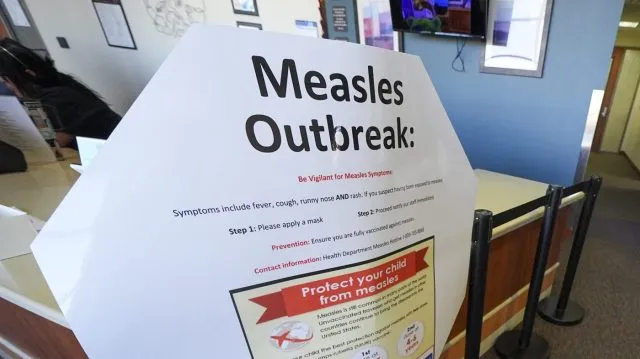

New outbreaks of measles, which had been considered eradicated in the U.S., may force colleges to rethink their vaccine strategies.

There is no standard way universities approach vaccine reporting, requirements or exemptions, with some given a far freer hand by their home states than others.

But in the face of rising vaccine skepticism, the University of Wisconsin-Madison announced last week it is shifting to require students to disclose their vaccination status, and it is possible that other schools may follow suit.

UW-Madison said students must tell the university their vaccination status for measles, mumps and rubella; tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis; chicken pox; meningococcal; and hepatitis B. The change came after a measles case on campus last month, but the school is not implementing vaccine requirements.

"Colleges and Universities in America are caught in a legal and political dilemma. Given the rapid rise of vaccine-preventable diseases including measles, colleges and universities should be increasing their vigilance of vaccine status among students, faculty, and staff," said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown Law.

The U.S. officially eliminated measles in 2000 but is at risk of losing its status after substantial outbreaks last year and so far this year.

Around 910 confirmed cases of measles have been reported as of last Thursday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), affecting nearly half of states.

"Schools that take shortcuts for the near term to just assume that students who went to school in a state that required those vaccines -- but they don't check those records -- could find themselves in a very difficult position, with a huge amount of work, uncertainty and fear and concern on their campus when measles walks onto the campus. So, preparing now can save them a huge amount of work and heartache and stress later," said Kelly Moore, CEO and president of immunize.org.

Ave Maria University in Florida is experiencing the largest campus measles outbreak in recent history, with more than 45 confirmed cases and nearly 60 students in quarantine.

"Academic institutions tend to be environments where infectious diseases can quickly spread. In one large classroom, many dozens of students can be confined in close spaces for prolonged periods of time. Under those conditions, even a single measles case is highly likely to spread widely across the campus, as students also live in close proximity with roommates in dorms and apartments," Gostin said.

"But at the same time, the political dynamics of forced vaccination are harsh," he added.

At least 34 states have laws on the books regarding vaccine requirements for universities, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). At least 22 states require the meningococcal vaccine, 23 require up-to-date measles vaccinations, 13 require up-to-date vaccination for diphtheria, pertussis and/or tetanus, and at least 10 require the hepatitis B vaccine.

Medical exemptions to these requirements exist in all states, and many have exemptions for religious or personal reasons, the NCSL reported.

"What keeps campuses safest are high levels of vaccines and whether it's through requirements or encouragement ... people don't really want to be told what they have to do. They do want to make decisions, but they want to have people who they trust help them make those decisions, people who have actually had time to be informed on the topic," said JoLynn Montgomery, chair of the American College Health Association's Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Committee.

"So, making sure that college campuses and college health centers are places filled with professionals who can be trusted by constituents, by the students and the faculty and the staff ... is really crucial," she added.

But requiring more vaccinations can be a tricky equation, especially given the likely pushback from the Trump administration.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, has long been skeptical of vaccines, although he did encourage parents to consider getting their kids the measles vaccine during last year's Texas outbreak.

Communities need a 95 percent vaccination rate to reach herd immunity against a disease.

"The health secretary has been equivocal at best about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. At the same time, courts are pushing for broad religious exemptions to vaccine requirements. The legal and political momentum is decidedly against compulsory vaccinations. That is a recipe for the continued unchecked spread of measles and other highly preventable infectious diseases," Gostin said.

The CDC found that in the 2023-24 school year, fewer than 93 percent of kindergarteners had all state-required vaccines, down from 95 percent in the 2019-20 school year.

But some say unless there is a huge outbreak, it is hard to imagine a big change to vaccine policies at the university level.

"It's not just that we largely eliminated measles in 2000; I think we eliminated the memory of measles. I think people don't remember how sick or dead that virus could make you," said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.